For many years, from the 1860s into the first few decades of the 20th century, one method utilized by the Indianapolis fire department to respond to fires was the use of fire towers. These towers traditionally, and predictably, were located on the top of the tallest buildings in the city, and manned by dedicated members of the fire department. The fire fighters would use their vantage point, and powerful field glasses, to keep an eye out for a wisp of smoke or a breakout of flames, sometimes a difficult task amongst the jumble of buildings, especially in an era when chimney smoke was a common feature on the city's skyline. Wondering what spotting a fire would look like? Below is an image of a residential fire just south of my home a few years ago. I spotted the smoke one morning before work and sent my drone up to see what was happening. While this fire sticks out in the dark of the morning, imagine the view without the flames, and dozens of other plumes of smoke rising from chimneys and smokestacks.

Various structures were used as fire towers for the city over the course of 60-70 years. The earliest purpose-built tower appears to have been constructed atop the Glenn's Block building in 1862-63. The building, which for many years hosted The New York Store, was only 4 stories tall, but at the time was one of the tallest buildings in the city. In addition to watching for fires, with the assistance of field glasses, the tower was also supposedly used to monitor the Confederate prisoners kept at Camp Morton, 20 blocks to the north. Whether that was even possible is questionable, considering the limited height of the tower. For fires, and potentially, escapes by traitorous prisoners of war, a bell was mounted on the back of the building for the tower’s occupants to alert the city. The bell would be rung a number of times corresponding to the city ward where the fire was located, although it was not an efficient system, and many times fire fighters arrived too late to beat back the fire. The image below (from the Indiana Historical Society) shows the Glenn's Block building with its fire tower on the south side of East Washington Street, between Meridian and Pennsylvania.

The next fire tower was the old Marion County Courthouse, the cupola on top of the clock tower being the highest point in the city when it was completed in the 1870s. The courthouse served this role into the 1900s. However, in 1912, the Merchants Bank Building on the southeast corner of Washington and Meridian Streets was completed. 17 stories and 245 feet high, the tower became the tallest occupied building in the city, although the Soldiers and Sailors Monument was still slightly taller, at just over 284 feet, thanks to Lady Victory, or Miss Indiana as she is sometimes called, on top of the monument.

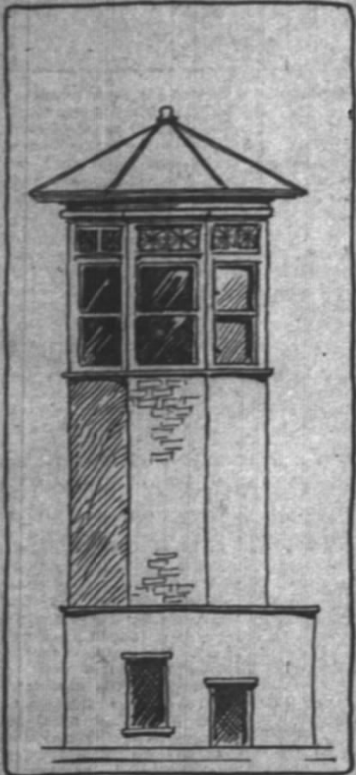

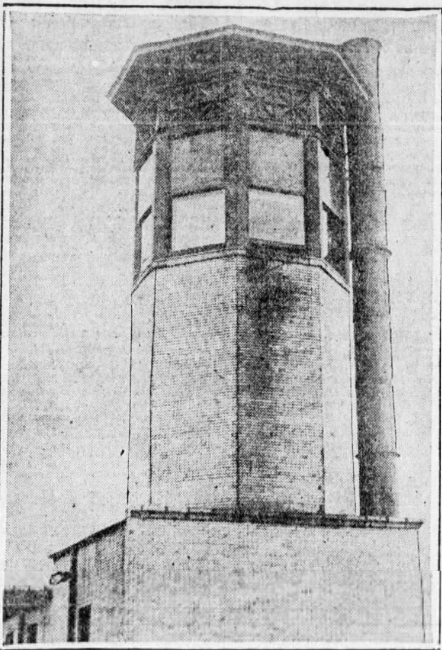

The fire tower which was constructed on the top of the bank building topped out higher than the Monument at 295 feet. The tower was first occupied by the city on January 1, 1913, with a contract between the city and Merchants Bank being finalized in February. The plan for the fire tower is shown below on the left, while the finished product is on the right. The tower was an octagonal shape, with a glass enclosed room perched at the top.

By the 1920s, four fire fighters took shifts in the tower. Famed Indianapolis Star reporter Mary Bostwick visited the tower and described the interior as "[a] neat, cozy little place," although she noted that in the summer the temperature inside reached 110 degrees. The room occupied by the firefighters had a rocking chair, swivel chair, and a table which was described to have a variety of tools, including field glasses, maps and charts, and a search light.

As of 1923, A.C. Reese had been the longest serving fire tower occupant, having been on the job for 31 years, serving at the Merchants Tower and the Courthouse before that. During a June 1923 interview with the Indianapolis Times, the reporter asked Reese if he ever got tired, being up in the tower all alone. “No indeed I’m always finding something new,” Reese responded. “As long as I’ve been here there isn’t a day passes, but that I see something I never saw before.” Reese explained that he would use landmarks around the city, including smokestacks, in order to identify, or approximate, where a fire was located. In 1922, the fire tower reported 198 fires. Field glasses were still used by the watchmen, while a telegraph connected the tower with city hall for alerts.

Even with the availability of telephones and other fire reporting systems, the fire tower continued to be used into the late 1920s. In 1927, the fire tower experienced one of the scariest moments in downtown Indianapolis: The tornado of 1927. The full history of that storm was covered in a blog post back in 2019. Even before this storm, which saw a tornado run across downtown and slam into the eastside, the tower was often heavily impacted by wind. Called a “wind catcher” by the Times, the tower had a noticeable vibration and sway during high winds.

When the tornado struck, the watchman on duty, Henry G. Cook, described how the heavy windows on the tower shattered. “These windows are double and the glass is the very heaviest of plate glass, yet in a moment they were as egg shells,” Cook said. Cook, and the tower survived the tornado, but the tower's future use was limited. In 1929 it was announced that the city would cease its use of the fire tower for fire detection purposes. The move was estimated to save the city $7,000 annually, mostly on salaries.

Once abandoned by the fire department, the watchtower found other uses, partly because the city’s contract for the tower did not expire until 1932. Almost immediately the tower was commandeered by the Indianapolis Smoke Abatement League, whose inspectors were to take daily surveys of smoke conditions in Indianapolis as part of an effort begun almost two decades prior to clean up the air quality of the state’s capitol city. The inspectors worked in conjunction with the city’s smoke inspector, who was armed with city ordinances addressing the smoke nuisance and would receive reports from the League’s observations. At the same time, a telephone line was still maintained on the tower, allowing the inspectors to contact the fire department in the event the smoke they spot was from a fire which needed the department’s attention.

This use was short lived. With the Merchants Bank building being the tallest building in the city, and the watchtower adding to that height, there was potential value in the burgeoning field of aerial navigation and the opening of the city’s new Municipal Airport in 1931. Transferring commercial air travel from nearby Stout Field, the airport, which sits on the location of today’s airport, would have airplanes flying over the downtown area.

To facilitate air travel in the area, and into the new airport, the fire tower was used as the foundation of this beacon, the tower itself enclosed within a steel lattice structure which would raise the beacon an additional 122 feet above the roof of the Merchants Bank building, and 375 feet above street level (in comparison, the antenna on the Salesforce Tower are 811 feet above street level) The beacon featured an illuminated “1-A-1” and an 18 foot arrow pointing towards the airport, and a “6” indicating the number of miles. The beacon was reportedly visible for 75 miles. The beacon’s tower had “LINCO” on each of its four sides. LINCO was short for Lincoln Oil Company, who had donated the beacon to the city. The beacon was lit on the evening of March 11, 1931, when Governor Harry Leslie hit a switch which had been set up at the Columbia Club for the event. Earlier in the day, the city was treated to a parade of dozens of aircraft, military, commercial, and personnel, which flew over the city (image below) to celebrate the beacon.

But beacon’s lifespan was limited. In August of 1939 the Times reported that the LINCO sign was coming down and the beacon was being disassembled. The fire tower itself was removed sometime in the mid to late 1940s. A red and white transmission antenna was placed on the roof of the tower for many years, and is visible in images from the November 5, 1973, Grant Building Fire. The first television broadcast of the Indianapolis 500 in 1949 was broadcast from atop the Merchants Bank Building. Today, the Merchants Bank building is known as the Barnes & Thornburg building, after the law firm that is the building’s main occupant and owner. The building was placed on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1982. While not visible from the ground, aerial photos and Google Maps show the remains of the tower: an octagon shaped foundation which sits on the square platform on the roof of the building.

Sources

Indianapolis Times: June 19, 1923, July 13, 1927, February 3, 1931, August 10, 1939,

Indianapolis News: July 12, 1912, March 21, 1925, September 5, 1929, July 12, 1939

Indianapolis Star: May 16, 1912, February 24, 1923, August 20, 1929, October 18, 1929, March 12, 1931, June 15, 1956,

Airplanes, over Merchants Bank with Linco Sign, 20 March 1931 (Bass# 219941), Indiana Historical Society,

Glenn's Block on Washington, Circa 1862 (Bass #31197 and #17806), Indiana Historical Society, https://images.indianahistory.org/digital/collection/dc012/id/15185/rec/15

Report of the Department of Public Safety, 1911, https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ffm/id/73163/rec/118

West Washington Street between Illinois and Meridian Streets, Indianapolis, Indiana, circa 1915, Indiana Album, Joan Hostetler Collection, https://indianaalbum.pastperfectonline.com/photo/4DBE4095-046E-4065-989D-086481199278

Comentários