“A Veritable Fire Trap”: The National Surgical Institute Fire of 1892

- Ed Fujawa

- Mar 28

- 13 min read

Updated: Apr 6

Note: As I was wrapping up research for this post early on the morning of March 28, I ran across a 2013 blog post by Libby Cierzniak which also covers this topic. If you are so inclined, you can check out that post here.

The northeast corner Illinois and Georgia Street today hosts the St. Elmo Steakhouse and Harry & Izzy’s restaurants, both part of the Circle Centre Complex. Long before any of these establishments were opened, and well before the construction of Circle Center, this location was the site of one of the worst disasters in the history of Indianapolis: The National Surgical Institute Fire of 1892.

The Surgical Institute was operated by Drs. Horace Allen and Charles R. Wilson, in 1892, but was first opened in Illinois in 1858, before moving to Indianapolis in the late 1860s. The Institute advertised itself as treating a variety of crippling physical diseases and injuries, with a focus on the orthopedics, although a wide variety of conditions were addressed. This was despite the practice of medicine in the mid and latter 19th century as being far from an accurate profession, which was fraught with guesswork and incomplete understanding of the human body, and technological limitations. Incorporated in 1869, the Institute at various times had satellite locations in Philadelphia, Atlanta, and San Francisco. In addition to treating patients on site (there were reportedly accommodations for 300 patients), the Institute also manufactured medical devices, such as splints and other assistive devices, on site for sale to patients on location and abroad.

The Institute advertised heavily, including detailed pamphlets which were available by mail order, like the one below, published in 1885 and available on the Internet Archive (link in 'Sources' below). The pamphlet proclaimed on its first page that the "institution was established for the cure of the lame and deformed, and of chronic diseases requiring its superior treatment."

Local newspapers also carried advertisements. An ad in the News on September 22, 1888, stated that “[p]arents should take their afflicted children to the National Surgical Institute, where every provision is made for their cure.” The ad goes on to detail various conditions which can be addressed, including paralysis, “spinal diseases,” lameness, as well as “tumors ulcers, abscesses, or chronic disease….”. The advertisement also alluded to some disagreement between the Institute and the greater medical community. “It is thought by some persons that the Surgical Institute and the members of the medical profession are hostile to each other. This is not the case. The Surgical Institute desires no patients for treatment by its methods which the family Physician is prepared to treat.”

In Indianapolis the Institute was based on the northeast corner of Illinois and Georgia Streets, a location it would occupy over the next 20 years. The engraved image at the beginning of this post shows that location. The Institute’s Illinois Street location was actually several connected buildings, with the main section being located directly on the corner of Georgia and Illinois, with frontage on both streets. This section of the Institute had been originally constructed in 1856 as a three-story hotel, although later owners slapped a fourth level on the structure, prior to the Institute taking over the property. The second section of the institute, or the annex, as it was sometimes called, fronted Georgia Street. A narrow alleyway separated the two sections, which were connected by a series of passageways and walkways. The 1887 Sanborn map shows this confused arrangement, with different parts of the Institute complex having two, three, or four stories.

The map also shows the walkways between the two sections being at various levels, i.e. 2, 3, and 4. Unfortunately, I have been unable to locate any photos of the institute, although, as shown above and below, illustrations of the complex are available.

The fire broke out shortly before midnight on January 21, 1892, when the Institute’s janitor/night watchman, George Finn, discovered the flames. The location of the flames varied depending on the reports in the various sources; initially, the fire was located in the secretary’s office, while other reports indicated the advertising office, although these may have been the same room. Wherever the fire originated, the situation quickly began to spin out of control. John Wilson, the Institute's landlord/superintendent was summoned when the fire was discovered and he ran to grab a fire hand grenade, essentially a capsule of water designed to be thrown upon small fires to extinguish the flames. However, by the time he returned with the grenade, the fire was reportedly too large.

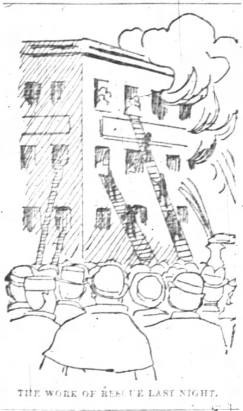

An alarm was raised using the fire box system, which called fire fighters from nearby stations. A chaotic scene greeted the fire fighters upon arriving and was described in detail by the News: “By the time the department arrived the scene was one to blanche stout hearts. Poor, helpless cripples were hanging on the fire escapes and in every window. The heart-rending cries of those shut in the burning building mingled with the shouts of the firemen and police.”

Rescue efforts began immediately. Firefighters and police officers entered the building and began to extricate patients. Passersby also assisted with the rescue, along with personnel from the Union Depot (Union Station) and the Louisiana Street streetcar barns, which were a short distance from the Institute. For the fire department, the blaze was the largest since the department’s experience at the Bowen-Merrill fire two years earlier in 1890. That fire, which struck the stationary and book company’s building at 18 West Washington Street, resulted in the largest loss of life for the Indianapolis Fire Department in its history when the top floors of the building collapsed, killing 13 firefighters.

At the Institute fire, efforts to save the patients continued. One fire fighter, Maurice Donnelly, who was not on duty at the time, but had just left the meeting of a local social club and happened to be nearby, ran into the building and emerged with two children, and a woman, whom he carried to safety on his back.

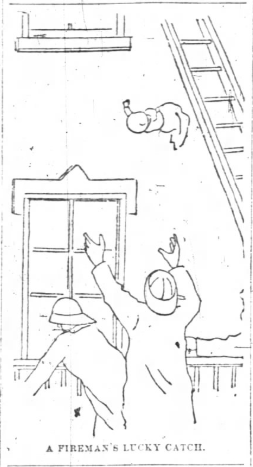

Some occupants of the Institute leapt from the windows of the multi-story buildings in a bid to escape. John Costello, a firefighter from the number 11 engine house (or number 4 depending on the source), caught a child who was thrown from the third floor by its desperate mother, as shown in the sketch on the left below from the Indianapolis News.

In a time before photographs appeared in newspapers, sketches were often used to illustrate newspaper stories. The Surgical Institute fire was heavily covered in local press, and all major newspapers featured sketches from the fire. I located no photos of the fire scene, either at the time of the fire, or its aftermath, so these sketches are the best visual evidence of the fire.

Returning to the plight of the patients in the Institute, one woman, Mrs. Samuel Lazarus, leapt from the third floor with her daughter, Lottie, in her arms. Mrs. Lazarus was severely burned across most of her body, and she suffered further injury in the fall. She was taken across Georgia Street to the Weddell House (a hotel located where the Omni Severin stands today), where she died around 4 am, not long after a rabbi arrived. Her daughter suffered a broken leg, and severe burns and was taken to St. Vincent Hospital in very serious condition, as were other survivors.

Fire fighters and passersby continued their rescue activities, using ladders to access the upper floors, or running straight into the Institute through its entrances. An institute employee, identified as Mrs. Thompson, who worked in the Institute’s nursery, had 43 children in her charge. She sought an escape route, but found only one, a stairway which was inexplicably blocked by a wire grate. She struggled with the grate, injuring her hands in the process, before she, with the assistance of police officers, managed to tear down the grate and escape the building with the children.

According to the Indianapolis News, a fire at the Institute had long been feared, due to the construction of the building, its haphazard updates through the years, and because of the patient’s housed on site, many of whom were crippled or otherwise unable to ambulate without aid. The News observed that any “[p]ersons who have been through the Surgical Institute can well understand the difficulty from it when on fire. The halls are narrow and winding, and what was worse, communication between the extreme of the long building was only possible by going up and down steep staircases.” Other news reports alluded to the poor condition of the building. The prior summer one of the Institute’s chimneys collapsed and fell onto the street below, narrowly missing pedestrians. Reports indicated that there had been no wind at the time of the collapse, and that poor construction was to blame. In October 1878, the then fire chief, J.G. Pendergast, on the orders of the city's Common Council, inspected the Surgical Institute, and found it unsafe in the event of fire:

The council passed a motion ordering the fire chief to inform the owners of the Institute (and the Grand Opera House and Metropolitan Theatre, which were also inspected) that their buildings were found to be lacking fire escapes:

Dr. Wilson responded to this inspection and committed himself and the Institute to install more fire escapes on their buildings. Writing in his history of Marion County and Indiana in 1910, Jacob Piatt Dunn recollected that the Surgical Institute building was “a veritable fire trap for sound people, let alone helpless cripples, including the upper portions of several old buildings connected by narrow and intricate passages, and insufficiently furnished with fire escapes.”

Rescue and firefighting efforts continued, although the rescue of patients became the only mission. Fire chief (or chief engineer as was the title then) Joseph H. Webster told the News that when he arrived on scene he could tell the structure was a loss. As described by the News, Webster “devoted all his efforts to rescuing the unfortunates who hung from every window with blanched faces, calling for help.” Many patients were rescued by the efforts of Webster and his fire fighters, police officers, and passerby’s. “It is remarkable that so many were saved,” said Webster. “How we ever got them out I do not know now.”

By 3:30 am the flames had been extinguished to a degree to allow police and members of the coroner’s office to begin a search of the building for remains. Unfortunately, not all the patients had been able to escape. The Indianapolis News provided detailed, and perhaps overly descriptive, reporting on the grisly scenes of burned remains, including how two young girls were found locked in an embrace, and were “burned almost beyond recognition.” The News also reported that “[n]ine bodies were taken out of the main building, all burned to a crisp.” Rescuers were shocked by the scenes they encountered, and “[t]hose who witnessed the horror will carry the remembrance to their graves,” observed the News. Sketches of the interior of the Institute appeared in January 23 edition of the Indianapolis Journal, as shown below. The captions read "chamber of death" and "hall in the east annex."

Even as rescue, or more accurately, recovery, efforts, were in progress, discussion began about who was to blame for the tragedy, with the owners of the Institute being the main focus. Dr. Wilson was questioned about this and stated that “[t]here is no blame that can be attached to us. We have an electric register and can tell if the watchman fails to make his rounds at stated intervals.” He continued, noting that “[p]ublic opinion will be against us and so will the press, but if we were taking these poor, helpless creatures here to do them injury, it would be different, but we take them here to do them all the good we can, and then when an accident occurs over which we have no control, we are blamed for it.” I find Dr. Wilson's rationale rather ridiculous, but Wilson continued to dig himself into a hole when asked about whether the Institute had insurance coverage. Rather conveniently, he noted that “I renewed my policies yesterday, but money is not what is worrying me now. I am able to stand such a loss.” The News detailed a long list of insurance policies which covered the property, whether recently expired, or allegedly in force, at the time of the fire. The main building alone had ten policies in place, worth $22,500. The other sections of the complex had a variety of policies as well.

Unfortunately, the number of casualties began to increase, and after searchers combed the ruined building, the remains of seventeen fire victims were located. The lead column on the front page of the Friday, January 22 edition of the Indianapolis News (which was an evening paper) and the Indiana State Sentinel recorded the names of the deceased, as well as those wounded, and at the time, those missing. Because of the Institute’s national reputation, and its tendency to attract desperate patients from other states, the dead were all from out of state. Searchers continued to comb the ruins all day Friday and into Saturday. Late Saturday, a final victim was located on the fourth floor; 6 year old Arthur Bayliss, who had been among the missing. Also late on Saturday Lottie Lazarus, whose mother had leapt from the building in an effort to save her, succumbed to her injuries. The final death toll was 19.

Investigation into the cause also began even as recovery efforts proceeded. Reports indicated that the fire had spread to the dining room on the third floor of the “annex,” which was the addition across a small alleyway to the east, fronting Georgia Street. The fire spread with “great rapidity” to the main building and soon both buildings were fully involved. The small room where the fire originated was described as an “advertising room,” and reportedly housed a large amount of paperwork, such as pamphlets and circulars, which provided excellent kindling, although what caused the initial spark remained a mystery. The walkways which connected the two buildings had been constructed of wood and not iron as would have been appropriate per city officials. It was opined that if this had been done the fire’s spread would have been prevented, although considering the size of the blaze, and the close proximity of the building, spreading of the fire seemed inevitable. Even while the wreckage still smoldered, and the injured were still being treated, Dr. Allen turned an eye towards rebuilding. He stated on January 23 that the building would be remodeled and rebuilt and even met with city officials about his plan.

The remains of those who died were taken to the several undertakers and funeral homes around the city for final arrangements, and crowds gathered outside each, consisting of curious onlookers, or family members seeking information on the deceased. Over the course of the day on Friday, and especially on Saturday the 23rd, the remains began to be shipped to their hometowns. Small boxes of personal effects, often charred and burned, were sent with the caskets. Most of the remains had been identified, although the Indianapolis Sun reported that as of Friday, one body remained unidentified due to the extensive burn injuries, and the Sun reported that same day saw the beginnings of an exodus of the uninjured patients from the city, as patients returned to their homes, with the aid of family members and friends.

In the aftermath of the fire an inquest was launched by Marion County coroner Frank Manker, a process which took four weeks. The Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, which was critical of the Institue’s owners and Manker, reported on the process of the investigation on February 10, 1892, noting that “[a] good deal of testimony has been laid before the coroner tending to show that the Surgical Institute building was a model, and that all the inmates were as safe against fire as the occupants of any other building in the city.” The Sentinel continued, stating that “[t]his is all very well as far as it goes, and if it were not for those nineteen dead bodies which accumulated within a few moments after the building caught fire it would be smooth sailing for the coroner, and he would have no difficulty in rendering a verdict such as the proprietors of the institute are anxious for."

On Sunday, February 21, 1892, Coroner Manker issued his decision, determining that the fire was an accident, and in assigning no blame to the Institute’s owners, stated that “the proprietors used more than ordinary precaution for the protection of the lives and property of their patients by providing ample fire fighting appliances, stairways exist and fire escapes…”. Manker further found that half of the deceased died of suffocation, while the deaths of the remaining victims, including Mrs. Lazarus and her daughter, “resulted from their inability to use the means of escape provided on account of fright, confusion of mind, and the awful suddenness with which the disaster came upon them.” Manker also determined that the buildings which constituted the Institute “were well provided with exits, fire escapes and facilities for fighting fire, and as safe as such building are which are not fire proof.” The staff of the Institute all did their utmost, and the various patients were generally aware of the layout of the building and the exits, although there was no written notice of the fire exits in the individual rooms, which Manker noted was a violation. Manker further observed that many of the dead were found in their rooms, and “few seemingly made an effort to escape, although in almost every one of such rooms other inmates who were more calm escaped.”

Manker’s determination of no fault on the management of the Institute was not popular in the city, and he was heavily criticized in the press, and he lost his race for reelection for the post a few years later. Meanwhile, the Indianapolis Fire Department was lauded for their efforts in fighting the fire and rescuing patients. The department's official history described how "[m]any of the firemen groped their way in deadly, stifling smoke, through narrow and intricate hallways to save the helpless cripples, and by these efforts, coupled with the efforts of those of the attendants who did not become incapacitated by fear, many, who would otherwise have been lost, were saved.”

As it turns out, the Surgical Institute did not continue operations on site of the fire but was instead moved to a new location on the northwest corner of Capitol and Ohio Streets, where it continued to operate. However, Drs. Allen and Wilson would apparently dissolve their partnership, as a notice appeared in the Indianapolis News on January 11, 1894, noting that Dr. Allen had no further interest in the National Surgical Institute at the location on Georgia Street. The notice was signed by Dr. Wilson. Whatever the circumstances of this break up, Dr. Allen opened the Institute, now bearing his name (image below), at the Capitol and Ohio Street location that same year. Within a decade the Institute ran into financial trouble which led to its closure. The remaining building was used as a hotel; first known as the Imperial Hotel and then the Roosevelt Hotel.

The buildings the Institute abandoned at the corner of Illinois and Georgia were partially repaired and rebuilt and continued to be used for a variety of other tenants over the years, including as the Stubbins European Hotel starting in 1894. The hotel would have its own fire in 1945 which resulted in one fatality. By the early 1950s, the location of the institute was a parking lot, while the buildings which now house St. Elmo's Steakhouse stood alone on the north end of the block. The site of the fire remained as parking lots until the construction of the Circle Centre Mall began in the early 1990s. The site as it appears today is shown below.

Sources:

History of the Indianapolis Fire Department, Indianapolis Firefighters Museum Collection, https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/ffm/id/1199/rec/1

Indianapolis News: June 26, 1891, January 22, 1892, January 23, 1892, January 25, 1892, February 12, 1892, February 22, 1892, April 4, 1892, January 11, 1894, January 29, 1894,

Indianapolis Sun: January 23, 1892, January 25, 1892, February 24, 1892

Indianapolis Journal: August 12, 1869, January 23, 1892, February 22, 1892

Indiana State Sentinel: January 27, 1892, February 3, 1892, February 24, 1892

The National Surgical Institute: Indianapolis, Ind. U.S.A (informational pamphlet), U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://archive.org/details/101532257.nlm.nih.gov/mode/2up

Indianapolis, Compliments of A.M. Ragsdale Co. (1907), https://www.digitalindy.org/digital/collection/IH/id/5075/rec/21

Proceedings of the Common Council, Board of Aldermen, City of Indianapolis, 1879, https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofco187879indi/mode/2up

Indianapolis police manual, 1895, https://archive.org/details/indianapolispoli1895indi/page/38/mode/1up

History of Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana, https://archive.org/details/historyofindiana00sulgrich/page/271/mode/1up?q=surgical+institute